Basic concepts¶

In this chapter we cover the essentials of Concrete Settings.

Defining settings¶

Defining settings starts

by subclassing the Settings

class.

Each setting is defined by

Setting descriptor.

The catch is that one does not have

to declare each setting explicitly.

Let’s start by defining AppSettings

class with a single boolean-type DEBUG setting:

from concrete_settings import Settings, Setting

from concrete_settings.validators import ValueTypeValidator

class AppSettings(Settings):

DEBUG = Setting(

True,

type_hint=bool,

validators=(ValueTypeValidator(), ),

doc="Turns debug mode on/off",

)

And here is the short version which produces the same class as above:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class AppSettings(Settings):

#: Turns debug mode on/off

DEBUG: bool = True

Though this does not truly comply with the Zen of Python

Explicit is better than implicit.

wouldn’t you agree that the short definition

is easier to comprehend?

The short definition looks like a boring class attribute

with a sphinx-style documentation above it.

Still, all the required details are extracted

and a corresponding Setting attribute is created.

The magic behind the scenes is happening in the metaclass SettingsMeta.

In a nutshell, if a field looks like a setting, but is not explicitly

defined as an instance of class Setting,

a corresponding object is created instead.

Later in the documentation the setting creation

rules are explored in-depth.

For now please accept that Concrete Settings’ preferred way of declaring

basic settings is by omitting the Setting(...) call at all.

Ideally a setting should be declared with a type annotation and documentation

as follows:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class AppSettings(Settings):

#: Maximum number of parallel connections.

#: Note that a high number of connections can slow down

#: the program.

MAX_CONNECTIONS: int = 10

You can also declare a setting as a method, similar to

a Python read-only property:

from concrete_settings import Settings, setting

class DBSettings(Settings):

USER: str = 'alex'

PASSWORD: str = 'secret'

SERVER: str = 'localhost'

PORT: int = 5432

@setting

def URL(self) -> str:

"""Database connection URL"""

return f'postgresql://{self.USER}:{self.PASSWORD}@{self.SERVER}:{self.PORT}'

print(DBSettings().URL)

Output:

postgresql://alex:secret@localhost:5432

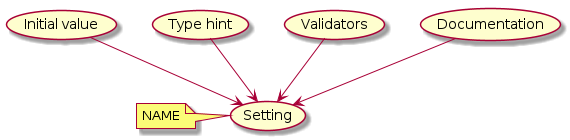

Before going further, let’s take a look at the contents of a Setting object. Each implicitly or explicitly defined setting consists of a name, initial value, a type hint, validators, and documentation.

Initial value is a setting’s default value.

Type hint is a setting type. It is called a hint, since it carries no meaning on its own. However a validator like the built-in

ValueTypeValidatorcan use the type hint to check whether the setting value corresponds to the required type.Validators is a collection of callables which validate the value of the setting.

Documentation is a multi-line doc string intended for the end user.

Reading settings¶

After a Settings object has been initialized successfully it can be updated

with values from different Sources, such as

YAML or

JSON

files,

enironmental variables

or a plain Python dict.

If none of the above fits your needs, check out

sources API for creating

a required settings source.

Updating is done by calling Settings.update(source).

For example, to update the settings from a JSON file:

{

"ADMIN_EMAIL": "alex@my-super-app.io",

"ALLOWED_HOSTS": ["localhost", "127.0.0.1", "::1"]

}

from concrete_settings import Settings

from concrete_settings.contrib.sources import JsonSource

from typing import List

class AppSettings(Settings):

ADMIN_EMAIL: str = 'admin@example.com'

ALLOWED_HOSTS: List = [

'localhost',

'127.0.0.1',

]

app_settings = AppSettings()

app_settings.update('/tmp/quickstart-settings.json')

print(app_settings.ADMIN_EMAIL)

Output:

alex@my-super-app.io

Validation¶

When Settings values have been finaly loaded, it is time to validate each and all settings’ values altogether.

A Settings object validates its setting-fields and itself when

Settings.is_valid()

is called for the first time.

Validation consists of two stages:

For each setting, call every

validatorofsetting.validatorscollection. This validates a setting value as standalone.Settings.validate()is called. It is indtended to validate the Settings object as a whole.

All validation errors are collected and stored in Settings.errors

from concrete_settings import Settings, Setting

from concrete_settings.exceptions import ValidationError

def not_too_fast(speed, **kwargs):

if speed > 100:

raise ValidationError(f'{speed} is too fast!')

def not_too_slow(speed, **kwargs):

if speed < 10:

raise ValidationError(f'{speed} is too slow!')

class AppSettings(Settings):

SPEED: int = Setting(50, validators=(not_too_fast, not_too_slow))

app_settings = AppSettings()

app_settings.SPEED = 5

print(app_settings.is_valid())

print(app_settings.errors)

Output:

False

{'SPEED': ['5 is too slow!']}

Type hint¶

Type hint is a setting type.

It is intended to be used by validators like the built-in

ValueTypeValidator

to validate a setting value.

Otherwise it carries no meaning and is just a valid Python object.

The ValueTypeValidator

is the default validator

for settings which have no validators defined explicitly:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class AppSettings(Settings):

SPEED: int = 'abc'

app_settings = AppSettings()

print(app_settings.is_valid())

print(app_settings.errors)

Output:

False

{'SPEED': ["Expected value of type `<class 'int'>` got value of type `<class 'str'>`"]}

Behavior¶

Imagine that you would like to notify a user that a certain setting

has been deprecated.

Raising a warning when settings are initialized and

every time the setting is being read - sounds like a plan.

A straightforward way to do this is by sublassing the

Setting class and overriding

Setting.__get__().

Another way would be using the supplied Settings Behavior mechanism - by “decorating” settings.

For example, let’s take a look at the built-in deprecated

behavior. It conveniently adds DeprecatedValidator

to the setting validators. The rationale of using the behavior instead of a validator is improved readability.

Just have a look:

from concrete_settings import Settings, Setting

from concrete_settings.contrib.behaviors import deprecated

class AppSettings(Settings):

MAX_SPEED: int = 30 @deprecated

app_settings = AppSettings()

app_settings.is_valid()

If Python warnings are enabled (e.g. python -Wdefault), you would

get a warning in stderr:

DeprecationWarning: Setting `MAX_SPEED` in class `<class '__main__.AppSettings'>` is deprecated.

In a nutshell, a behavior is a way to change how a setting behaves

during its initialization, validation, reading and writing operations.

A behavior is attached to a setting via @ operator:

value @behavior0 @behavior1 @... and by decorating property-settings:

from concrete_settings import Settings, Setting, required

from concrete_settings.contrib.behaviors import deprecated

class AppSettings(Settings):

MIN_SPEED: int = 30 @deprecated @required

@deprecated

def MAX_SPEED() -> int:

return 100

A very handy validate behavior

can be used to rewrite the example with validators as follows:

from concrete_settings import validate

class AppSettings(Settings):

SPEED: int = 50 @validate(not_too_fast, not_too_slow)

Nested settings¶

Nesting is a nice and simple way to logically group and isolate settings. Let’s try grouping database, cache and logging in application settings as follows:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class DBSettings(Settings):

USER = 'alex'

PASSWORD = 'secret'

SERVER = 'localhost@5432'

class CacheSettings(Settings):

ENGINE = 'DatabaseCache'

TIMEOUT = 300

class LoggingSettings(Settings):

LEVEL = 'INFO'

FORMAT = '%(asctime)s %(levelname)-8s %(name)-15s %(message)s'

class AppSettings(Settings):

DB = DBSettings()

CACHE = CacheSettings()

LOG = LoggingSettings()

app_settings = AppSettings()

print(app_settings.LOG.LEVEL)

Output:

INFO

At first glance, there is nothing special about this code.

What makes it special and somewhat confusing is

that class Settings is a

subclass of class Setting!

Hence, nested Settings behave and can be treated

as Setting descriptors - have validators, documentation

or bound behavior.

Additionally, validating top-level settings automatically cascades to all nested settings. The following example ends up with a validation error:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class DBSettings(Settings):

USER: str = 123

...

class AppSettings(Settings):

DB = DBSettings()

...

app_settings = AppSettings()

app_settings.is_valid(raise_exception=True)

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

concrete_settings.exceptions.ValidationError: DB: Expected value of type `<class 'str'>` got value of type `<class 'int'>`

Combining settings¶

Another way of putting settings together is by using Python’s multi-inheritance mechanism. It it very useful when putting a framework and application settings together. For example, Django settings and application settings can be separated as follows:

from concrete_settings import Settings

from concrete_settings.contrib.frameworks.django30 import Django30Settings

class ApplicationSettings(Settings):

GREETING = 'Hello world!'

class SiteSettings(ApplicationSettings, Django30Settings):

pass

site_settings = SiteSettings()

print(site_settings.GREETING)

print(site_settings.EMAIL_BACKEND)

Output:

Hello world!

django.core.mail.backends.smtp.EmailBackend

Another use case is extracting settings to own classes and combining them to mimic flat legacy settings module interfaces. For example, let’s combine Database and Log settings:

from concrete_settings import Settings

class DBSettings(Settings):

DB_USER = 'alex'

DB_PASSWORD = 'secret'

DB_SERVER = 'localhost@5432'

class LoggingSettings(Settings):

LOG_LEVEL = 'INFO'

LOG_FORMAT = '%(asctime)s %(levelname)-8s %(name)-15s %(message)s'

class AppSettings(

DBSettings,

LoggingSettings

):

pass

app_settings = AppSettings()

print(app_settings.LOG_LEVEL)

print(app_settings.DB_USER)

Note that Python rules of multiple inheritance are applied.

For example validate()

must be explicitly called for each of the base classes:

class AppSettings(

DBSettings,

LoggingSettings

):

def validate(self):

super().validate()

DBSettings.validate(self)

LoggingSettings.validate(self)

What’s next?¶

Now that you know the basics, why not to try adding Concrete Settings to your application? A minimal user-friendly setup is shown in Start me up section.